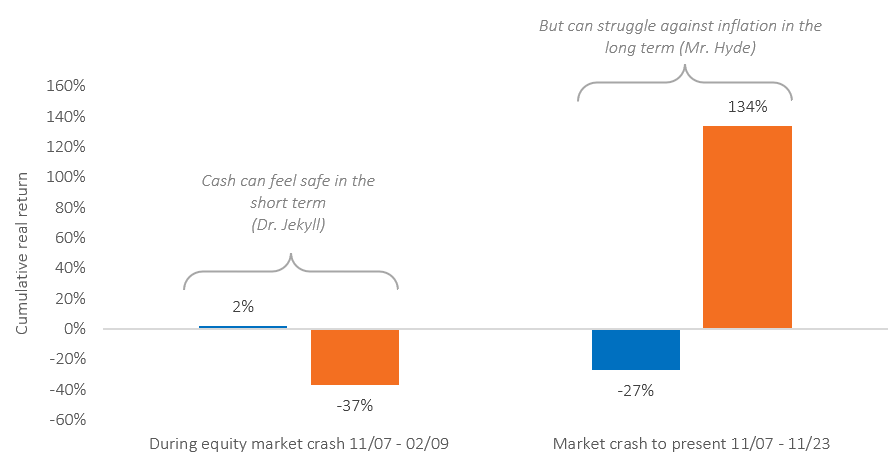

Cash is the Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde asset class of the investing world. Its good Dr. Jekyll moments tend to come at times of market turmoil, such as in 2022 when bonds and equity markets both fell. Its evil Mr Hyde persona is its terrible track record of maintaining or growing purchasing power over time for investors. The chart below demonstrates how cash performed during the Global Financial Crisis (2007-2009) and how it has performed since then, compared to world (developed and emerging) equities. Over the whole period, 27% of its purchasing power was eroded, whilst ‘higher’ risk equities’ purchasing power more than doubled, even when measured from the height of the market before the fall.

Figure 1: Cash does not fall like equities, but it can be a poor store of long-term value

Source: Morningstar Direct © All rights reserved (see endnote). Indices: ICE BofA SONIA Overnight Bid, MSCI ACWI. Adjusted by: UK CPI. Data in GBP terms.

It can feel tempting to want to hold cash that pays a seemingly decent rate of interest, but the problem is that no-one rings a bell telling you when to get out of risky markets and into cash, or when to get back into markets.

‘The idea that a bell rings to signal when investors should get into or out of the stock market is simply not credible. After nearly fifty years in this business, I do not know of anybody who has done it successfully and consistently. I don’t even know anybody who knows anybody who has done it successfully and consistently. Yet market timing appears to be increasingly embraced by mutual fund investors and the professional managers of fund portfolios alike.’

John Bogle, Founder, Vanguard Group and the grandfather of index investing

In 2022, when bonds and equities both fell, driven to a large extent by the rapid rise in inflation to double digits and the subsequent increase in both bank base rates (controlled by central banks) and bond yields (driven by the markets need to be compensated for risks taken on),

some investors were tempted to retreat to cash. After all, deposit holders could receive, say, 5% or so on their cash, so why bother with bonds or even investing in general?

Answering the bond question, it should be remembered that, on average – as with placing a bank deposit – the longer you lend your money for (which is what you are doing when you give the bank your money or buy a bond) the higher the interest rate or yield in the case of bonds. So, for a long-term investor, this ‘term’ premium should provide a small higher expected long-term return. In addition, often but not always (2022 being a case in point), at times of equity market crisis money tends to flood out of risky assets and into high quality bonds, driving prices up. In this case, investors revive both capital gains and yield. This provides a defensive fillip not available to those holding cash, who just receive the interest they are paid.

Perhaps something also worth noting is that it is very difficult to second guess where bond yields will be in the future. There is quite a bit of talk in the media that interest rates – being the bank base rate – may come down in the next year. That is in each central bank’s control. Bank deposit rates are generally set relative to this rate. Bond yields, on the other hand, are driven by the market’s aggregate view of the risks it perceives, which will already incorporate its own collective view on where the bank base rate will be in the future. It is not the case that bond yields will fall, just because the bank base rate is reduced, as that is already anticipated to some extent and reflected in bond prices today. No market timing bell there. Trying to second guess the market is a challenging sport with few winners. In the US, for example, over 90% of government bond funds failed to beat their market benchmarks over a 10-year period[1].

In terms of not investing at all, Figure 1 above makes the case pretty strongly as to why long-term investors should avoid holding cash in lieu of investing. If we look at the period since the start of 2023, an investor holding cash, which may have felt comfortable at the start of 2023, would have left valuable returns on the table, as Figure 2 below illustrates.

Figure 2: Holders of cash have missed out since the start of 2023 (to 31-Jan 2024)

Source: Morningstar Direct © All rights reserved (see endnote). Cash – Royal London Short Term Money Mkt Y Acc, SDGB – Bloomberg GblAggxUSMBS 1-5Y FA TR HGBP, SD Corporate Bonds – Markit iBoxx GBP Corp 1-5 TR, UK equity – MSCI United Kingdom NR USD, World equity – MSCI ACWI NR USD.

Anyone hear the market timing bell? No? Then stay invested.

Risk warnings

This article is distributed for educational purposes only and should not be considered investment advice or an offer of any security for sale. This article contains the opinions of the author but not necessarily the Firm and does not represent a recommendation of any particular security, strategy, or investment product. Reference to specific products is made only to help make educational points and does not constitute any form or recommendation or advice. Information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable but is not guaranteed.

Past performance is not indicative of future results and no representation is made that the stated results will be replicated.

Use of Morningstar Direct© data

© Morningstar 2024. All rights reserved. The information contained herein: (1) is proprietary to Morningstar and/or its content providers; (2) may not be copied, adapted or distributed; and (3) is not warranted to be accurate, complete or timely. Neither Morningstar nor its content providers are responsible for any damages or losses arising from any use of this information, except where such damages or losses cannot be limited or excluded by law in your jurisdiction. Past financial performance is no guarantee of future results.

[1] SPIVA U.S. Scorecard Year-End 2022 – available at www.spglobal.com.